Two days to go, and my mind won't settle

A deviation from my usual newsletter

I sat at my desk yesterday morning with a pot of black tea. I was ready to write, but my mind wouldn’t settle. I kept thinking of the time when I worked for an arts education nonprofit where a part of my job was to run a year-long weekly writing workshop at a public school.

In 2016, the project’s genre focus was memoir. At the start of the year, the 5th graders’ memoirs were almost universally about the school’s overnight camping trip in Virginia; a family trip to Six Flags theme park that summer; or the death of a beloved family pet. Since they were ten- or eleven-years-old, these topics made sense. The students labored diligently for weeks crafting their narratives, learning about things like memoir’s double “I”; sensory descriptions in setting; and capturing dialogue. September turned into October, then October became November.

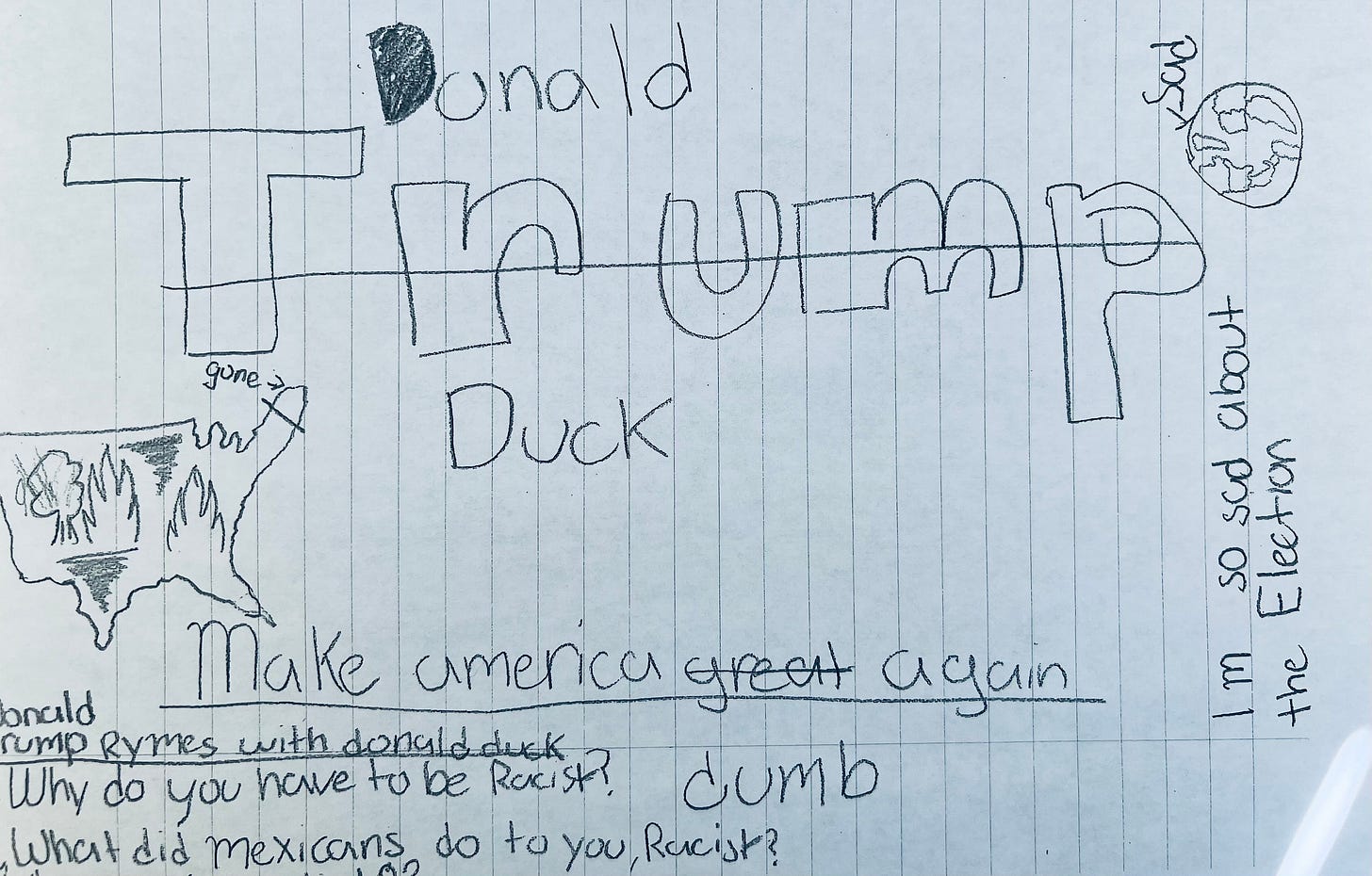

Throughout the fall, the 2016 U.S. presidential election was in the air, and it was not unusual to overhear the kids talking about “Donald Duck,” their pejorative for Donald Trump. The presidential election was an undercurrent to everything, the way oxygen runs through our veins but we don’t notice it until we’re short of breath. We had been collectively short of breath for months. The 5th graders were familiar with the candidate’s racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric—language that specifically targeted them and their families, as they were all either Latinx or Black first-generation U.S. citizens or immigrants, and a few were undocumented—but they were also just kids. They zipped around the playground at recess, complained about homework, and gave me earfuls about their favorite video games and YouTube stars.1

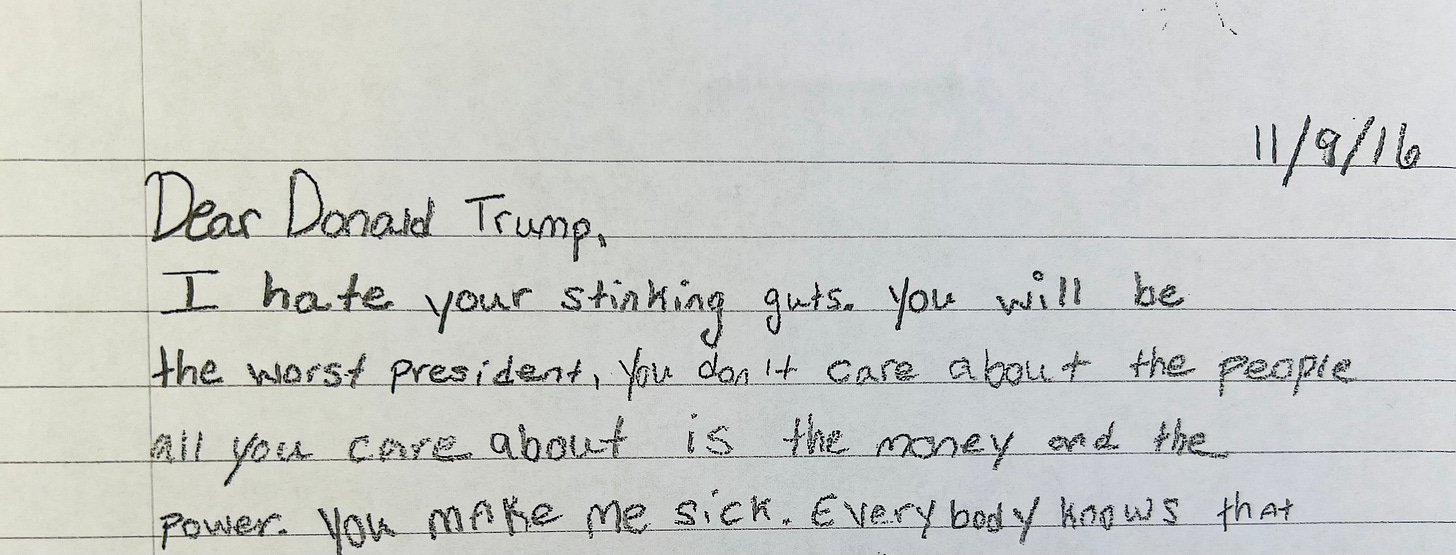

On the bright, cold morning of November 9, 2016, the day after Trump won the election, the students arrived to school red-eyed from crying, red-faced with anger and betrayal. J. demanded to know why we, the voting-age adults in the room, had let everyone down. L. asked, in Spanish, how soon the deportations would start. Her mom was undocumented and L. was U.S. born; she added stoically that she hoped to spend one last Christmas with her mom before they were separated.

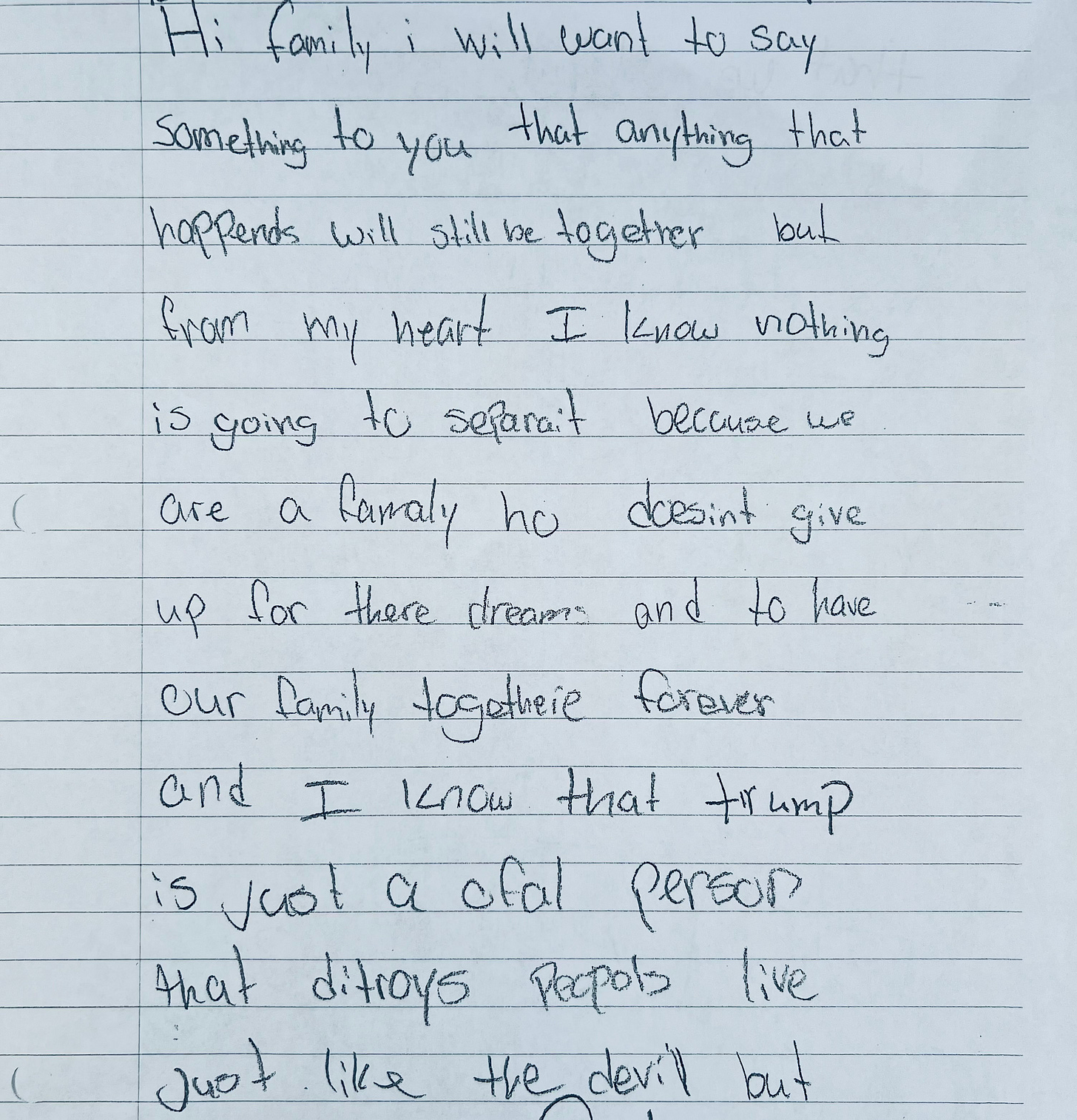

That day, we didn’t do memoir. I opened up space for emotional processing instead. Whatever they felt they needed to express they would write down, and then we would share them aloud. Students bent over their sheets of wide-ruled paper, pencils scribbling. They demanded answers. They pleaded with the president-elect to be rational, kind, and honest. They insulted and mocked him. They called him a r^pist and wrote f^ck Trump. They drew pictures of apocalyptic visions. They expressed disappointment that they weren’t witnessing the first female president. They told their families that they loved them no matter what happened. They repeatedly wrote about their sense of powerlessness, how much they wished they were 18 and old enough to vote.

I’ve been thinking about those kids again, now eighteen or nineteen and able to vote in a presidential election for the first time. The more I’ve seen people—especially people with privilege—publicly declare that they’re not voting, or that they’re voting for a third-party candidate because Kamala Harris isn’t perfect, the more I am returned to that day of deep grief and fear those 10-year-olds experienced, children who had no power to affect their lives. Children who had to watch the adults around them make choices that left them vulnerable and afraid.

There will be enormous and possibly irrevocable consequences for a great number of vulnerable and marginalized people—including children here and abroad—if Trump is re-elected. He has promised as much. His former staffers and advisers have said it. We have already lived during one presidency of his, and we continue to live with its after-effects.

The classroom teachers photocopied the students’ letters and gave them to me. Seventy-three in all, from three classrooms of 5th graders. I re-read them this morning when I couldn’t write. The letters are raw and emotional. They are angry, confused, mournful, and occasionally hopeful. A protest anti-Harris vote is disconnected from the reality of a Trump presidency, one that we’ve seen before. That isn’t a path of change or hope. But with Harris, we have no idea what’s to come. And I choose to dwell in that possibility. I hope you will, too. '

100% of the students qualified for free/reduced lunch, the federal indicator of childhood economic poverty. For most of them, English was their second language and was not the primary language spoken at home. The public school system and nonprofits often label such students “at-risk," “underserved,” “underprivileged,” or “under-resourced.” Outside of K-12 education spaces, most folks use the label marginalized.

A beautiful note and I couldn’t agree more! Xox